1. Fees, fees, fees

For every $100 you invest in whole life insurance, the first $5 goes to purchasing the insurance itself; the other $95 goes to the cash value buildup from your investment, Ramsey says. But for about the first three years, your money goes to fees alone.

Someone is making out, and it’s not your beneficiary.

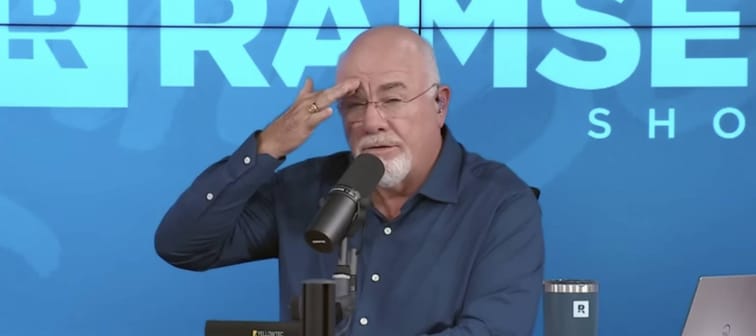

“It’s front-loaded as an investment,” Ramsey said. “That isn’t necessarily evil in and of itself but is frowned upon in the financial investment world by and large.”

2. Lousy returns

OK, but you have life insurance your whole life, right? Well, it doesn’t get much better after the first three years. The average rate of return after those “three years of zeroes” will be about 1.2% on that $95, according to Ramsey.

“Let’s be generous and say it’s double that,” he said. “It’s still not a good long-term investment. If I could get 2.4% on my money market I’d be dancing a jig, but not on my long-term investments.”

Those figures, Ramsey noted, need to be north of 10% to beat inflation and taxes.

“That makes it absolutely horrendous,” he contended. “Decades ago, the financial community moved by and large towards investing in term life for the $5 from the $100, and doing almost anything else with the other $95 — but over in the investment world instead of the insurance world.”

What’s more, whole life insurance fee structures rob you of money power because the sacrificed cash denies you the compound interest you’d see through traditional investing. Additionally, insurance companies could refuse to refund any of your money if you can no longer keep up with the payments.

3. Guess who gets most of the dough when you die?

The stake in the heart for whole life insurance is that when you die, the insurer keeps your money. That’s right: they absorb the cash value of your policy while survivors receive the leftovers in what’s called a “death benefit.” The policyholder can only use the cash value while they’re alive.

It’s enough to make you wish you had insurance on your whole life insurance. Here are some better ways to put your retirement allocations to work.

Alternative one: Term life

As Ramsey mentions, term life insurance makes for a far better option than whole life insurance. Term life refers to a purchase that lasts for a period of time — maybe 10, 15 or 20 years — and guarantees payment if a person dies within that term.

With its restricted period of time, term life insurance is much cheaper than whole life insurance. Note that it only provides a death benefit and premiums depend on your age and health status. Know also that you can’t invest the money elsewhere — and don’t get it back if the term expires and you’re still alive. Consider coupling term payments with investments that will grow alongside them.

Alternative two: 401(k)

A 401(k) offers another financial buffer in the event of death. Yet, here’s the problem: many Americans don’t even have a 401(k), including those who freelance.

The good news for those with full-time jobs is that your employer may match your 401(k) investment, usually up to 6% of your paycheck. That’s free money toward your retirement. Let’s repeat that: free money.

Financial advisers can then help you invest that retirement cash. Further, you get a tax break for investing in the 401(k), as you won’t be levied on those contributions until you make withdrawals. This could be when you retire or want to hand it down to a beneficiary.

Alternative three: Roth IRA

The beauty of any individual retirement account (IRA) is that you can start one even if you already have a 401(k). With a Roth IRA, you’re taxed up front. This benefits you when you withdraw cash, as you’ve already paid the tax: What you take is what you keep (unless, of course, you use it to buy some whole life).

As with a 401(k), you can invest in any stock or index fund tied to the market to grow your funds. You can open one any time you want and hold it for as long as you want. Withdrawals must be taken after age 59½ and/or after a five-year holding period.

Bottom line: It’s wholly your life

With so many options to save for the future and your loved ones, there’s no reason to sink your whole nest egg in whole life insurance. It’s what big insurers are betting you’ll do — but as Ramsey might put it, you’d be better off washing out an orange marmalade jar instead.

“Put the money in a freaking fruit jar,” Ramsey quipped. “At least it’s there when you die!”